You have no items in your shopping cart.

0

You have no items in your shopping cart.

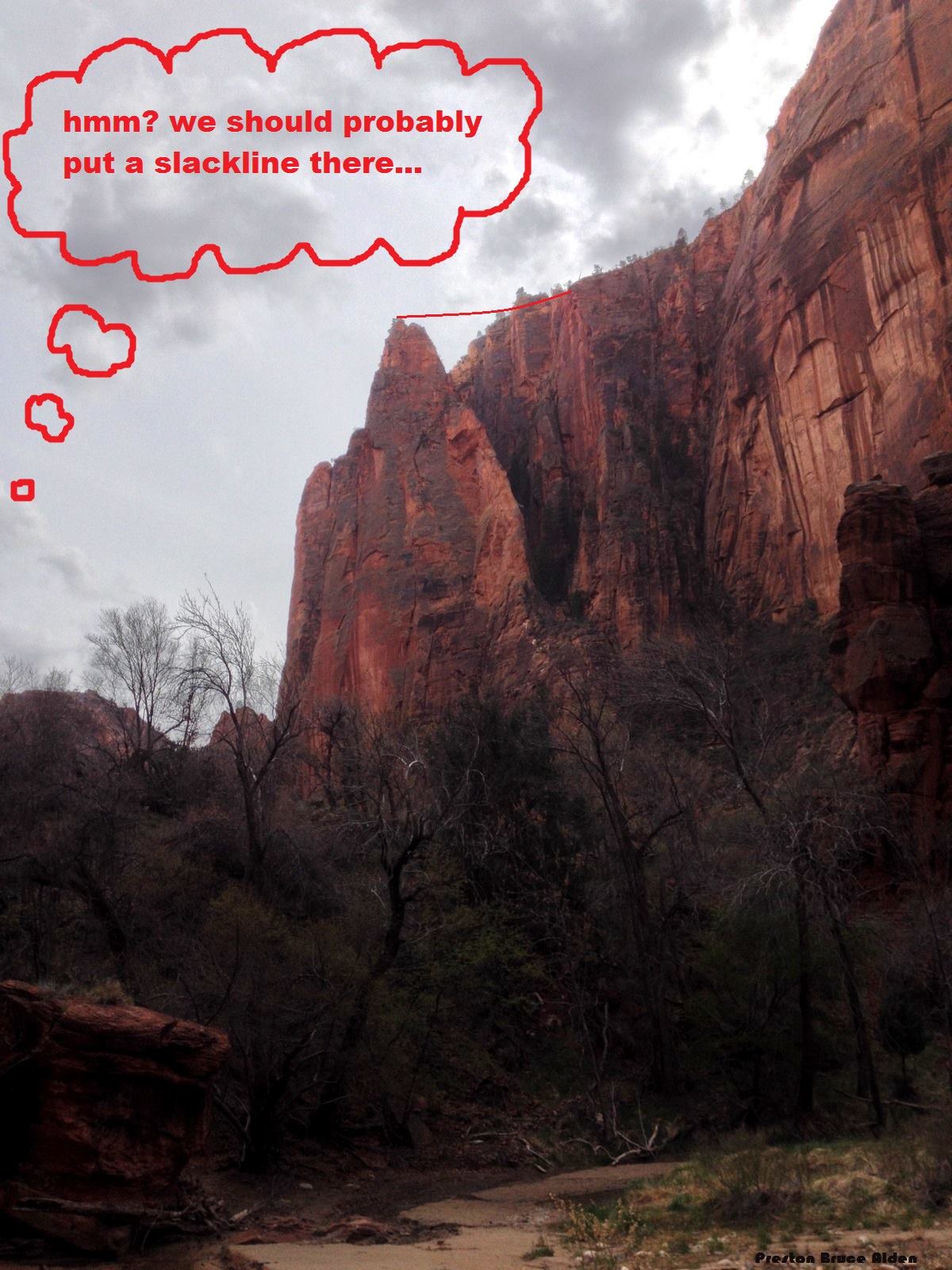

“Preston, we’ve been meaning to tell you that you’ve been getting a little too epic and not enough gnar”, said Susan. “This is an intervention.” We were standing around Susan and Jerry’s kitchen, and we’d just come up with the epic-gnar dichotomy to describe two approaches to slacklining. Gnar is rigging the same line in your backyard or nearest park or crag over and over again, getting totally dialed at outrageous tricks, surfs, bounces, or even just walking. Most trickliners fit into the gnar category, but my favorite examples of getting gnar would be Chris Rigby sessioning his personal backyard 280’ highline at the late great backyard highline festival house, and Jerry’s seemingly unstoppable march towards longer and longer highlines at the Consumes River Gorge (CRG). Epic, on the other hand, is characterized by long approaches, heavy loads, and likely some suffering, all in pursuit of a difficult to rig line, often with natural anchors. The rigging party is sometimes too tired to walk the line more than once before it is time to derig and schlep everything back out again. However, the line is usually in a spectacular location, and the photos can be mind blowing. Preston himself is one of the poster boys for the epic highline rig, and many of his projects in Tuolumne and the Sierras are well documented and very inspiring.

Susan’s intervention notwithstanding, we were getting ready for a trip that seemed to mostly hold promise of epicness. Preston had sold us on the idea of taking an exploratory highline trip to Zion National Park, home to an endless supply of multi-thousand-foot sandstone cliffs, beautiful scenery, and questionable rock quality. My friend Carl and I had flown from Seattle to Sacramento to meet up with Preston and Jerry in Davis. At the last minute, Jerry’s business obligations forced him to bail, which threw the logistics of the trip into uncertainty. Fortuitously, at just that moment Chris Wilson and his friend Milea got in touch with us looking to join a highline adventure. Everything fell into place, and so there we were, checking over our gear lists and getting ready to hit to road for the long drive from northern California to southern Utah.

Due to last minute packing and excitement about the trip ahead, I had hardly slept the night before our early morning flight. After we convened at Jerry’s house and then started the drive, I expected to pass out and nap in the car. Instead, Preston and I started talking and scheming about the potential goals and challenges of the trip. At some point, the conversation turned to questions of bolting and style. Zion National Park is a traditional climbing area, where bolting is discouraged unless absolutely necessary. Hand drilled bolts are allowed, but most climbing routes in Zion are protected with removable gear. Where would highlining fit into this picture?

The question of when and where it is appropriate to place bolts in rock has been a topic of active and sometimes contentious debate in rock climbing for some time. Highlining is a relatively new activity that seeks to use many of the same resources that are used by climbers. It is up to the slackliners to understand why bolting is controversial in climbing, and the solutions that have emerged in the climbing community that attempt to minimize conflict. This is especially true for slackliners looking to rig lines in an area with an active climbing community, and an established culture about bolting. Highlining is growing quickly, and if we want to preserve our access we need to learn how not to step on toes. Additionally, there are questions of style that are unique to highlining. Everybody involved in the sport now has the opportunity to help define one of the early eras of highlining style best practices.

Like Preston, I am also a trad climber, so I didn’t need any convincing of the value and satisfaction that can be had from climbing a route using only removable protection that you place yourself. On the other hand, I was a little less sure about the intrinsic value of a highline with natural anchors. Once you’re tied in and walking, I thought, isn’t the line itself the only thing that matters? In trad climbing, placing and evaluating gear becomes part of the movement and zen of the climb, but the only way I could imagine a natural highline anchor contributing to the walking experience would be if you were worried that the anchor might fail, and that did not seem like it would be a positive change. Nevertheless, Preston spoke enthusiastically, almost reverently, about his experiences with naturally rigged highlines. Maybe there was something I was missing. He also had a lot of good things to say about the largest size tri-cams, so I wasn’t totally sure about his mental state.

After a solid chunk of driving and a bivy in the desert, we were finally driving through the gate to Zion. We parked Preston’s truck at our campsite, and all piled into Milea’s compact sedan for our first drive into the canyon. The size of the sandstone formations was hard to comprehend as we craned our necks and tried to take it all in through the windows of the moving car. Every wall and spire seemed to hold endless possibility. The choices were almost overwhelming, but at the same time it was impossible to tell from the car if we would ever be able to get to any of these high up places.

We needed to do some recon on foot. We decided to devote at least the first day or two to explorations without carrying all the heavy highline gear. The next morning, we hiked up the extremely popular Angel’s Landing trail. After a mile or two, we gratefully diverged from the near conga line of tourists onto a less used trail. This trail soon brought us near the canyon rim, and looking down into the valley the scale of the place finally started to come into focus for me. Looking up at the cliffs from the car window was too much like looking at a postcard. From up high, the view made my chest swell with the size of the mountains and the vastness of the spaces between.

I made my way onto an outcropping that diverged from the cliff, and scrambled down and across a small gap to climb onto a boulder. A steep gully separated the end of the outcropping from the main cliff face. I stood on the boulder and pointed across the gully towards a point on the main cliff that was about level with my position. Here was a monster line possibility. Preston brought the laser over, and measured the gap to be about 280 feet. The exposure was more than 1000’ nearly straight down to the valley floor.

This gap captured our imaginations, but it was too early in the day and the trip to settle on an objective. Also, we all felt that a starting with something smaller would be better. We kept hiking, finding and evaluating gaps for their aesthetic qualities and whether safe anchors could be found. We carried a bolt kit, but Preston was reluctant to use it, and anyway we found no gaps that were crying out for bolted anchors.

We ended up hiking for quite a ways, chasing schemes about how to get on top of this or that formation. When we eventually turned around and headed back we still had not found our ideal first Zion line. We stopped for a snack near a side canyon that we had evaluated earlier in the day and marked as “maybe” for some tree anchor possibilities. Preston was scrambling around checking out the base of one of these trees when he called back to us about a big metal spike in the rock. I joined him, and sure enough there was a 1 inch diameter rod protruding from the rock. Curious. A short distance away I discovered three more rods close together, with their ends bent into circular eyes. It almost looked like an anchor for something. Could it be? I looked across the canyon, and level with where I stood I thought I saw another group of three rods.

These anchors seemed like a gift that could not be ignored. Still, we debated the wisdom of relying on the metal rods as highline anchors. They looked and felt absolutely bomber. However, we had no idea why they were placed, or what their history had been. From an engineering perspective, it was hard to imagine that somebody would place metal of that thickness into the rock unless it was designed to hold a significant load. With 3 rods per side (one per side was even extra beefy) we eventually made the judgement that the rods were as safe or safer than anything else we were likely to come across or place in the rock ourselves.

So we finally found our first Zion highline, and the rigging was simpler than we could have possibly imagined! We decided it must be a world record for weird discovered anchors. We returned the next day with our type-18 mkII and pulleys, and only one spanset per side with static rope to do individual backups to the eye of each rod. The line went up without a hitch, and soon we had a send train going with all four highliners walking successfully one after another, with many shouts of “CRUUUUSH” from Chris. Carl got on the line in an extremely bright pink pair of shorts. We may have given him too much encouragement because “Hot Pants Carl” would not get on another slackline without the hot pants for the rest of the trip. We called the line Iron, Lion, Zion, 166 feet long, 200 feet high, with one of the coolest exposure turn views I’ve ever seen.

I couldn’t believe that after only two full days in the park, we had already put up a rad enough line for me to consider the trip a success. We decided a rest day was in order. We set out to relax on a sandy beach by the river, but predictably, we soon found and rigged a nearly sensible water line. Chris has been telling stories about some of his projects with certain friends that were dubbed “fuckshit” lines, I guess based on what you might say while walking, rigging, or falling off. Our line went over soft sand, shallow water with rocks, and then alternately deep pools and large rocks. There were maybe two places where you could comfortably fall off the line into the water. It was relatively close to the ground though, so we judged it to be only minorly a fuckshit line. We all walked it anyway to keep the “CRUUUUSH” alive. Also it was probably a world record.

The monster line that we had scoped on the first day weighed heavily on our discussions of what to do next. The line was inspiring, and very intimidating. It would be a new personal record for any of us. We thought that if we were going to give it a try, it should be soon. The weather, however, had different plans. We had been having ideal spring conditions: sunny skies without extreme heat, but now it looked like a storm was rolling in over the next day or so. We decided a less committing project would make more sense.

We chose a side canyon more or less at random and started hiking, carrying a pared down rig and a shorter piece of doubled up type-18. The ground was flat and sandy in the bottom of the gully, and although the sky was grey and threatening, the scenery was beautiful. After an hour of hiking and scouting, we settled on a line between two trees across the gully. We soon had the line rigged, but as Preston scooted out for the first walk, the wind arrived. Violent, unpredictable gusts, and Preston riding the bucking line like the cowboy that he is, shouting at the sky. We all did battle with the wind, and soon with the rain and sleet as well. The line was never tensioned very much to begin with, and by the time we were done it hung across the gap with 2 or 3 feet of standing sag. A real storm rodeo. By the time we derigged and started walking out, a steady rain was falling. We scrambled down newly slippery rocks to regain the narrow, sandy bottomed gully, and admired a waterfall that hadn’t been there on our walk in. Suddenly, we realized that the waterfall was quickly turning our idyllic sandy path into a creek. We were ill prepared for wading, but a few hundred feet ahead we could see the leading edge of the new creek moving away from us. Time to get out of there! We ran and jumped from rock to rock and tried to overtake the moving water. Success! Back on the sand, we stayed in front of the flood and made it back to the car, thoroughly soaked. Back in town, in dry clothes and over pizza, we dubbed the new line “How to Outrun A River”, 156 feet long, 60 feet high.

The next day in camp as we waited for our stuff to dry, we discussed what to do next. Were we ready to attempt the big line? Our epic credentials had been pretty well established throughout the week, but walking a gap like that would require a considerable amount of gnar as well. Our trip was nearing its end, with time for only one more big push. It was time to go out of our comfort zone and give this a try.

As I lay in my tent that night, I tried to visualize the movements of a big double type-18 line under my feet, preparing my reflexes to respond to the waves in the line. Too soon, it was morning and were were grabbing our bags and hitting the trail with our earliest start of the week. The sky was light, but the sun would be hidden by the canyon walls for several more hours, and the Angel’s Landing trail was deserted. Despite the heavy load, I felt like I was floating up the hill, finding a natural maintainable rhythm.

We arrived at the gap and began building the anchors. First, we used a 300ft 9mm static rope to create a giant cordelette style anchor on the tensioning side of the line. We ran the rope back and forth around 3 different trees set way back from the edge. I am always distrustful of trees growing on rocky terrain, especially near the edge of a cliff. One has to wonder whether the roots have found solid purchase, or simply spread themselves out over the rock, holding no better than the sandy soil. We used three solid looking trees, way far back from the edge, and we wrapped the rope near the base of the trees to minimize torque on the root systems. The anchor was huge, but simple to understand, and utterly bomber.

Preston and Carl started the process of getting a tag line across the narrow top of the gully, and walking it down to our gap. I walked around to the static side of the line, back to the large boulder I had stood on when I first saw the gap. My mission was to somehow wrap the boulder, which was the size of a small RV. With about 80 feet of spansets and another 80 feet of static rope, Chris and I set to work. About 2 hours later, after way too much fiddling and redoing, the boulder was securely wrapped, and all abrasion points thoroughly padded. It was time to pull the line across, and add some tension.

The vision that we had on our first hike was now a reality. I don’t think we realized what we had found on that first day; it took the rest of the week of exploration to realize that this was one of the most prominent, easily accessed gaps in the park. Even better, the landscape offered solid natural rigging options. I had no doubts about the safety of the line, but the question remained whether any of us could walk it.

Finally, it was time to tie in and step out over the void. I felt the usually butterflies in my stomach as I sat on the line, trying to match the reality to my controlled visualizations the night before. I stood up and watched the waves from my motion travel away and back. I had to immediately catch the line, but in the brief moment of standing my body started to become attuned to the natural frequencies of the webbing at this particular length and tension. I stood up again, and this time I absorbed the initial motion of the line, and started walking. The longer I stayed up, the more I learned about how to keep going. Soon it became a matter of quieting my internal dialog, forcing myself to stay focused without overthinking. As I made progress, the space below me kept growing more vast and empty. I fought through waves of height induced adrenaline shivers, and somehow kept walking. The far anchor was suddenly... not so far. Keep walking, no thoughts of achievement, just feel the line. At last I can let it all go, yelling in relief and dropping to grab the weblocks. I made it! I couldn’t even believe it. I climbed past the weblocks onto the boulder where I had stood a week before, imagining the moment I was now experiencing. It was unreal.

The walk back was no picnic. Somehow the visual exposure was even more drastic in this direction, with the far wall dropping vertically for hundreds of feet below where the line left the cliff. I made it across, but it wasn’t pretty. One more goal left on the line, to send it both ways and demonstrate full mastery of the gap. For now, I just couldn’t believe that this line that had loomed so large in my mind had already been crossed. It was time for my friends to have a go at this beast of a line.

There were no other sends that day, but it was awesome to watch Carl walking long sections of the line, bounce sit starting, and of course showing off the hot pants. Chris has an approach to walking big lines that I find very admirable. He rarely sets himself the goal of sending the line, but rather goes straight for the fun stuff, bouncing and surfing. When he feels solid he sends hard, but he always has a good time, avoiding the frustrations of failing to meet an arbitrary goal. Preston unfortunately was not feeling his highline best that day, instead choosing to focus his efforts on capturing these amazing images.

Throughout the rest of the day I felt a glow of satisfaction, partly from having achieved my goal of walking this line and setting a new personal record, but mainly from the place, the light and the views, and the people I was sharing it all with. There is no way this could all have been arranged in advance, but that day was also my birthday. I turned 28 on March 28th, and sent a 286 foot highline. We considered naming the line Golden 28 or something like that, but I am always in favor of puns so instead we went with Pulpit Fiction. The name references the fact that when we found the gap, we thought we were exploring a formation called The Pulpit. This assumption, however, turned out to be fiction. The Pulpit is actually a small rock tower way down on the valley floor, visible from our line.

We left the rig up overnight and returned very early the next day. Preston took his best photos of the trip of us walking in the morning light, and I wrapped up my last piece of unfinished business, successfully walking the line in both directions. It was just icing on the cake at that point.

As we derigged, the landscape transformed back to its original state. At the beginning of the trip, I had been sure that I would want to place some bolts to establish a line that we could come back to, and to make the rig as safe as possible. Now I was very pleased by our all natural rig. For one thing, bolts would not have made our line any safer; the anchors we used were plenty strong enough. But the bigger question for me is: what, if anything, is betterabout a bolt free rig? I still stand by my opinion that the walk itself cannot be changed in any positive way by the choice of anchors. What this trip made me realize is that there is a bigger picture to consider; that the whole process of a highline trip is a cohesive whole, the planning, scouting, carrying loads, and sleeping out under the stars. From this perspective, rigging naturally can be a huge part of the experience. The anchor we created for Pulpit Fiction was really a work of both art and engineering. Similar to trad climbing, the process of working with the materials you carry and the features the landscape provides can be very enjoyable in its own right.

It comes back to the epic/gnar distinction. If you just want to get gnar, you’re usually looking for the shortest approach and the easiest rig available. Bolts are often (not always) ideal for these purposes. On the other hand, if you are looking for an epic highline trip, it may be best to leave the bolt kit behind and bring a pack full of static rope, big slings, and a rack of tri-cams. Actually, I learned a lot from Preston on this trip, but I’m still not convinced about the tri-cams.

← Older Post Newer Post →